The Real Reason of Suicide Of Indian True Farmer: Apathy, Agony, and Indebtedness?

While growing up in the state called “Wheat Bowl of India”, I remember there were many times when my parents and other community elders on festivities often ask us “Pray to Bhagwan Ji that we have a good Monsoon this year otherwise it will have a ripple effect on our life, especially our budget”. As a child, I often wonder how monsoon or rain is related to our Family or its budget but when I started working, I very well understood how monsoon impacts low and middle-income families in India.

It has been 74 years since the British left India but still, India is an agrarian country with around 70% of its population depending directly or indirectly upon agriculture for their livelihood. The agriculture industry contributes more than 15% to India’s GDP.

It is well-known fact that farmers in India irrespective of their state often refer to their agricultural produce as “Gamble of the monsoon”, which means it is too much dependent on nature so whenever there is a failure of monsoons, the crops fail as still, irrigation facilities are not much developed in India

Post-Independence, the only ruling Party which has ruled India most of the time was Congress. And by 1991, Congress has been in power for almost 42 years. Congress Government’s Poor Economic Policies, Inefficient Public Sector Units, and the Resulting Trade Deficits had led to the worst economic crisis in 1991 which Indians have witnessed in history. As the economic crisis was resulted from leading to balance of payments crisis so it is often also called “Balance of Payment Crisis”. This Balance of Payment Crisis had moved India to the brink of a sovereign default. The sharp depletion in India’s forex reserves — at less than $6 billion, was just enough to meet around two weeks of the country’s imports.

At such a critical juncture, Indian prime minister Shri P.V. Narasimha Rao Ji along with finance minister Manmohan Singh bought some economic reforms to pull the country’s economy out of a slump.

It did prove that the reforms by the Narasimha Rao Ji government to make India a liberalized, privatized, and globalized economy has helped a class (mainly middle and upper) of Indians live their dream life.

However, on other hand, these economic reforms did engulf a great many unsuspecting farmers in problems that were beyond their comprehension. India’s vast sections of the peasantry and rural populations have been a tumultuous and deathly period, like a never-ending recession after the reform implemented in the mid-1990s. It is very sad to mention that these reforms triggered the suicide cases that have only surged in the early 2000s[1]

In 2008, While I was scrutiny the Newspaper on my way to Office in Gurugram, I come across one news published on one corner of the inside page which reads as “One more Farmer commits suicide in Maharashtra”. Every day in almost every newspaper, we can find the News of Farmers committing suicide in some parts of India, however, the biggest irony is that neither such news finds its way to the Frontpage of any newspaper nor on Prime-Time News Media.

Let’s quickly go through that how many of our breadmakers committed suicide in the last couple of years.

On March 24th, 2008, 55-year-old farmer Shri Krishna Kalamb committed suicide. Just two days before hanging himself to death he penned his own eulogy – all of six lines – and put it in his shirt’s pocket.

In chaste Varhadi, a dialect of Marathi spoken in the western Vidarbha region that the British called Berar, begins thus:

Me aagala vegala, mahi nyarich jindagani;

mahye maran bhi aahe, jase avakali paani.

I am unique; my life an uncommon odyssey;

My death will also be like untimely rain.

Kalamb, a 5-acre, atypical, dry-land farmer from Vidarbha, a region in the news since 1995 for farmers’ suicides, wrote that his cotton was precious to him, as his poems. He likened its roots to the sweetness of sugarcane. In the poem, he built an image of his body hanging from a door – he had made up his mind to commit suicide.

Symbolism and emotion mark Kalamb’s poignant poems; he ended his life at his sister’s home in Murtijapur town, 30 kilometers from his native village Babhulgaon (Jahangir) in Akola. It is one of the six districts in Maharashtra – all in western Vidarbha – with a high incidence of farmer suicides. He left behind five daughters and a bereaved wife.

Like most farmers, he had unpaid debts from banks and private lenders and worried about the impending costs of his daughters’ weddings. A few years earlier, a devastating accident had left him with a limp. He could no longer physically work the way he used to in his heyday, which added to his frustration and financial woes.

In another poem, titled “Vasare” (Calves), he writes:

Amhi vasare vasare, muki upasi vasare

Gaya panhavato amhi, chor kalatat dhar

Tapa tapa gham unarato, unarato bhuivar

Moti pikavato amhi, tari upasi lekare[1]

We are calves—dumb, hungry calves

We tend to cows, but thieves walk away with the milk and cream

We sweat and sweat on fields, we cultivate pearls,

But our children go hungry.

There was a growing perception among the rural peasantry in Vidarbha that the new economic realities-imposed couple of years back were doing them more harm than good. Cotton farmers, for example, saw their production costs multiply many times as energy, inputs, and fertilizer prices soared. While generally the cost of living – health, education, and so on – went up, their real incomes stagnated.

As per one report in India, one farmer committed suicide every 32 minutes between 1997 and 2005[2].

According to the National Crime Records Bureau of India reported in its 2012 annual report, that 135,445 people committed suicide in India of which 13,445 were farmers. Farmer suicides account for 11.2% of all suicides in India[2].

Of these, 5 out of 29 states accounted for 10,486 farmers’ suicides. According to a report by the National Crime Records Bureau, the states with the highest incidence of farmer suicide in 2015 were as below[2].

| State | Total Farmers who committed suicide |

| Maharashtra | 3030 |

| Telangana | 1358 |

| Karnataka | 1197 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 581 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 516 |

| Punjab | 1000s |

| Chhattisgarh | 854 |

Maharashtra is by far the epicenter of the crisis with over 10,000 recorded farmer suicides between 2011 and 2013. Almost 75% of farmer suicides have occurred amongst small and medium farmers.

Nearly 4,00,000 farmers committed suicide in India between 1995 and 2018, if we collate the data from the annual reports of the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) on “Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India”.

Now Let’s drill down who are the people in the Agriculture sector who are committing suicide.

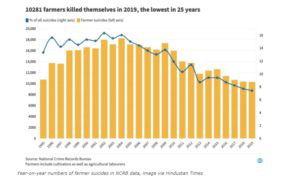

At least 10,281 persons involved in the farm sector ended their lives in 2019, accounting for 7.4 percent of the total number of suicides in India which was 139,516, suggests the Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India report 2019 by the National Crime Records Bureau[3].

The 2019 figure is marginally lower than 2018 when 10,348 people took their lives. The story, however, changes when one looks at suicides committed by farmers/cultivators, which is 5,957 as against 5,763 in 2018 — a three percent increase between 2019 and 2018.

| State | Total Farmers who committed suicide |

| Maharashtra | 3927 |

| Karnataka | 1992 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 1029 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 541 |

| Chhattisgarh | 499 |

| Telangana | 499 |

The above top six states account for 83 percent of the deaths committed by persons involved in the farm sector.

As per the NCRB report, farmers/cultivators are the people who are farming either on their own land or on leased land, with or without the assistance of agricultural laborers. Surprisingly, landed farmers accounted for 86 percent of the suicides, while the remaining 14 percent were landless farmers.

The number of suicides by farm laborers, defined as those whose primary source of income is through farm (agriculture/horticulture) labor activities, has gone down to 4,324 in 2019, from 4,586 a year before.

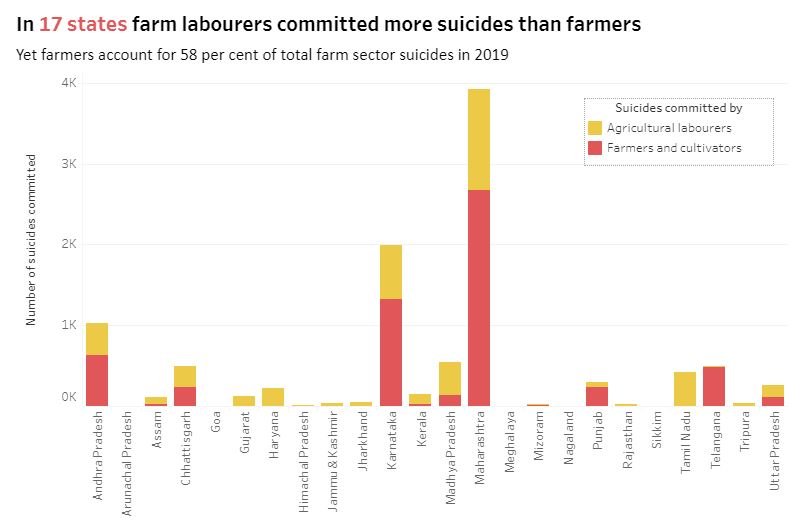

The numbers highlight another worrying trend. In 17 states, more farm laborer has committed suicides than farmers, while the reverse is true for seven states. Yet, only 58 percent of the total suicides committed by people employed in the sector are farmers.

West Bengal, Bihar, Odisha, Uttarakhand, Manipur, Chandigarh, Daman & Diu, Delhi, Lakshadweep, and Puducherry reported zero suicides of farmers and agricultural laborers [3].

The report suggests that with over 139,123 registered suicides, India recorded the highest suicide numbers in the past five years. The 2019 suicide numbers were 3.4 percent higher than in 2018. In other words, 10.4 people committed suicides per 100,000 population.

The prevailing agrarian distress has a context with many factors:

Local farmer’s markets were invaded by global markets, like that of cotton or food. Rapid upward economic mobility of sections of the population was creating newer inequalities, leading to a perception among the peasantry that they were losing out. The fast-changing economic conditions were also altering long-held social equations.

Landed farmers, once among the respected classes in a village economy, were now unable to meet their ever-growing needs, while the non-landed classes, absorbed in the unorganized service economy, migrated out of their villages to urban centers for better wages and work, doing marginally better than they once did as a farm laborer.

As the agrarian crisis has been one of the worst disasters to have hit India in the last couple of decades, there are many other reasons why farmer suicides happen. Many social, economic, political, and individual crises have forced them to end their lives. and because of this, they have to take heavy loans for growing crops and later they kill themselves due to their inability to repay loans mostly taken from landlords and banks. Thus, the indebtedness of farmers is one of the main reasons driving them to commit suicide. From 1991 to 2001, the indebtedness of farmers has grown by two times[2].

Other factors which heavily contribute to Indian Farmer’s suicide are Crop failure; Inability to sell the crops grown; Disappointing realization of prices. Sense of loss and depression.

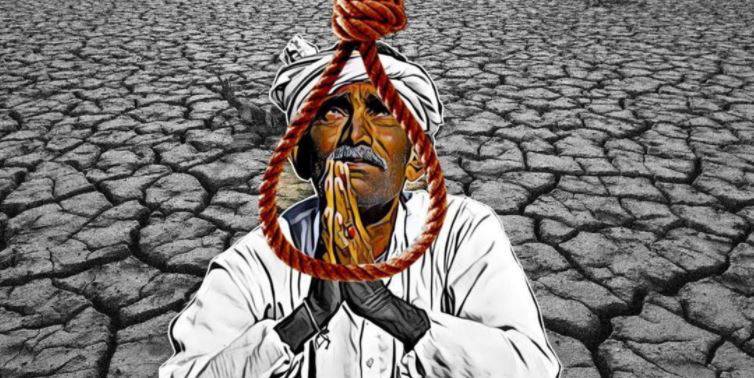

Not to mention here, family pressure is too high for farmers, they fail to make ends meet and thus commit suicide because of this failure. When a farmer commits suicide, compensation is facilitated by the farmer’s family.

However, another plight in the suicide case is that when female farmers commit suicide they are not compensated as they are not recognized as ‘Farmer’.

INDEBTEDNESS WAS THE REASON BEHIND THE SUICIDE OF 93% OF FARMERS.

The suicide of farmers which is complex and manifold is caused by various reasons which can be traced back to economic and policy changes during the 1990s.

The problem starts with the availability of timely credit. The banking sector is not ready to provide credit or loans to agriculture for avoiding risk.

Agriculture credit became a low priority, with some committees suggesting withdrawal of credit support to farmers.

Credit for housing and buying a car is available at a 9% to 11% rate of interest while the crop loans to the farmer are 17%. This shows the lack of government support for the farmers in the past.

The chasm has grown so vast that the farmer does not care if it does not rain one season, affecting farm yields and pushing inflation.

Agriculture has been practiced in India for ages, it is called the backbone of the Indian economy. Agriculture is the process of utilizing the land for growing different varieties of crops. Though farmers feed the nation, their conditions are far from satisfactory. All the economic development in a country like India is possible only if, the farmer’s community is taken care of on a priority basis.

The Indian government from the past 7 decades needs to answer “What happened to our farmers? Why did they kill themselves? Farmers like every human being have dreams, what will happen to their dreams? How do the farmers survive hunger, debts, sudden and extreme climate events, price volatility, poverty, structural inequalities? What are the factors which drive them?

[1] Statistics say nearly 4,00,000 farmers committed suicide in India between 1995 and 2018. Why? (scroll.in)

[2] Farmer’s suicides – An issue of great concern (indiatimes.com)

[3] Every day, 28 people dependent on farming die by suicide in India (downtoearth.org.in)

DISCLAIMER: The author is solely responsible for the views expressed in this article. The author carries the responsibility for citing and/or licensing of images utilized within the text.